Have you ever visited that friend — maybe it was your uncle or grandmother or a new love interest — that person who’d walk you through their house pointing out things? They’d pick up a knit pillow here, a ceramic bud vase there, a funny wooden children’s toy from the bookshelf — and tell you the story behind each of them. Where it came from. Why it’s there. How that knit pillow was going to be a baby blanket for the friend who miscarried. And those ceramic vase-looking things. They’re small insulators for an electric fence pilfered from the Birkenau concentration camp. Each object is intertwined with a story and a meaning for this person. Their house exists as a big book, keeping all of these stories together.

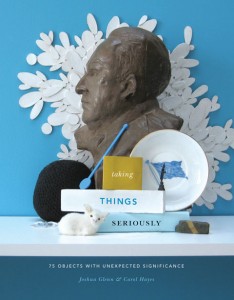

Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects With Unexpected Signifigance. Edited by Joshua Glenn & Carol Hayes, 2007.

I suspect that we all are a little like this. Us humans, we can’t stop telling stories. Objects often act as indexes for these stories.

There’s a wonderful book, Taking Things Seriously, that’s filled with photographs of quotidian objects and their owners’ stories about them. These tales are in turns funny, macabre, tawdry, revealing, and personal. In addition to this eminently browsable collection, the editors offer an introduction filled with words like ‘quiddity’ – the essence of a thing that differentiates it from other things. The implication being that this essence is the narrative manufactured by personal interaction with the object.

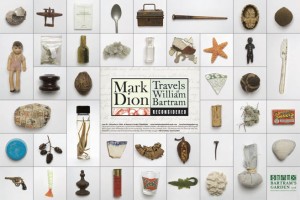

His presentation of these artifacts owes quite a bit to the Wunderkammers of Renaissance Europe. The creators of these cabinets, forerunners of modern museums, didn’t distinguish between science, art, history, ‘real’ and ‘fake’ – they mashed it all up and put it on the same shelf together. Daring viewers to find their own relationships – their own stories in these objects. Mark Dion continues this tradition. By presenting the interesting juxtapositions and similarities in his finds without any additional text, Dion removes the authorial voice of the historian or anthropologist, and makes way for his viewers’ stories about these objects. By virtue of the way that they’re presented, the objects almost beg the viewer to tell stories about them.

DHARMA Initiative mug as seen on screen on the TV series Lost.

So far we’ve been talking non-fiction, but tellers of fictional stories have plenty to think about when it comes to objects as attested by every ‘Carcetti for Mayor‘ t-shirt or DHARHMA Initiative mug. This (licensed and unlicensed) merchandise is generally produced after-the-fact and seems almost peripheral to the story from which it originates. But really, it’s not peripheral at all. Although I doubt J.J. Abrams gave them much thought, those DHARMA products let viewers of the series be part of the world of Lost. Now it’s no longer a world bound up behind a screen, it’s just as tangible as any other ceramic hot beverage container. Of course, there are storytellers that did give a little more thought to the way objects might allow their audience to occupy the same world as their story. Cathy’s Book and Personal Effects: Dark Art both give readers things to hold and touch in the same way the characters did. Even moreso, the button participants took away from attending a campaign rally for Harvey Dent (as part of the Why So Serious ARG for The Dark Knight) stood in for the entire experience long after it had wrapped. The story – the participant’s story – lives on embedded in that button. That t-shirt or mug or tattoo of the House of Baratheon are physical manifestations of beloved narratives. They allow their owners to dwell in a place in which the fictional narrative world intersects with ‘real’ lived experience.

Another lovely word from Taking Things Seriously: the Victorian concept of ‘notional’ to describe an inanimate object that “demands attention and exercises power over those people to whom it appeals.” There’s a sort of talismanic quality to that term. That, because of the narrative imbued in it, the object has a pull or gravity all it’s own. The Victorians were all over talismanic objects (with their hair jewelry) and so it’s a fitting era for a new project by Haley Moore, Laser Lace Letters, that puts physical objects at the center of a steampunk narrative. She’s coined a term for this form: ‘Tangible Storytelling.’ And if you’re quick, you can be one of the first publishers of this format by supporting her Kickstarter campaign.